Chapter 9 Package development

9.1 Why you need to write your own package

One of the reasons you might have tried R in the first place is the abundance of packages. As I’m writing these lines (in November 2020) 16523 packages are available on CRAN (in August 2019, there were 14762, and in August 2016, when I first wrote the number of packages down for my first ebook, it was 8922 packages).

This is a staggering amount of packages and to help you look for the right ones, you can check out CRAN Task Views.

You might wonder why the heck should you write your own packages? After all, with so many packages

you’re sure to find something that suits your needs, right? Well, it depends. Of course, you will

not need to write you own function to perform non-linear regression, or to train a neural network.

But as time will go, you will start writing your own functions, functions that fit your needs, and

that you use daily. It may be functions that prepare and shape data that you use at work for

analysis. Or maybe you want to deliver an analysis to a client, with data and source code, so

you decide to deliver a package that contains everything (something I’ve already done in the

past). Maybe you want to develop a Shiny applications using the {golem} framework, which allows

you to build apps as packages.

Ok, but is it necessary to write a package? Why not just write functions inside some scripts and

then simply run or share these scripts (and in the case of Shiny, you don’t have to use {golem})?

This seems like a valid solution at first. However, it quickly becomes tedious, especially if you

have multiple scripts scattered around your computer or inside different subfolders. You’ll also

have to write the documentation on separate files and these can easily get lost or become outdated.

Relying on scripts does not scale well; even if you are not sharing your code outside of your

computer (maybe you’re working on super secret projects at NASA), you always have to think about

future you. And in general, future you thinks that past you is an asshole, exactly because you put

0 effort in documenting, testing and making your code easy to use. Having everything inside a

package takes care of these headaches for you, and will make future you proud of past you. And if

you have to share your code, or deliver to a client, believe me, it will make things a thousand

times easier.

Code that is inside packages is very easy to document and test, especially if you’re using Rstudio.

It also makes it possible to use the wonderful {covr} package, which tells you which lines in

which functions are called by your tests. If some lines are missing, write tests that invoke them and

increase the coverage of your tests! Documenting and testing your code is very important; it gives

you assurance that the code your writing works, but most importantly, it gives others assurance

that what you wrote works. And I include future you in these others too.

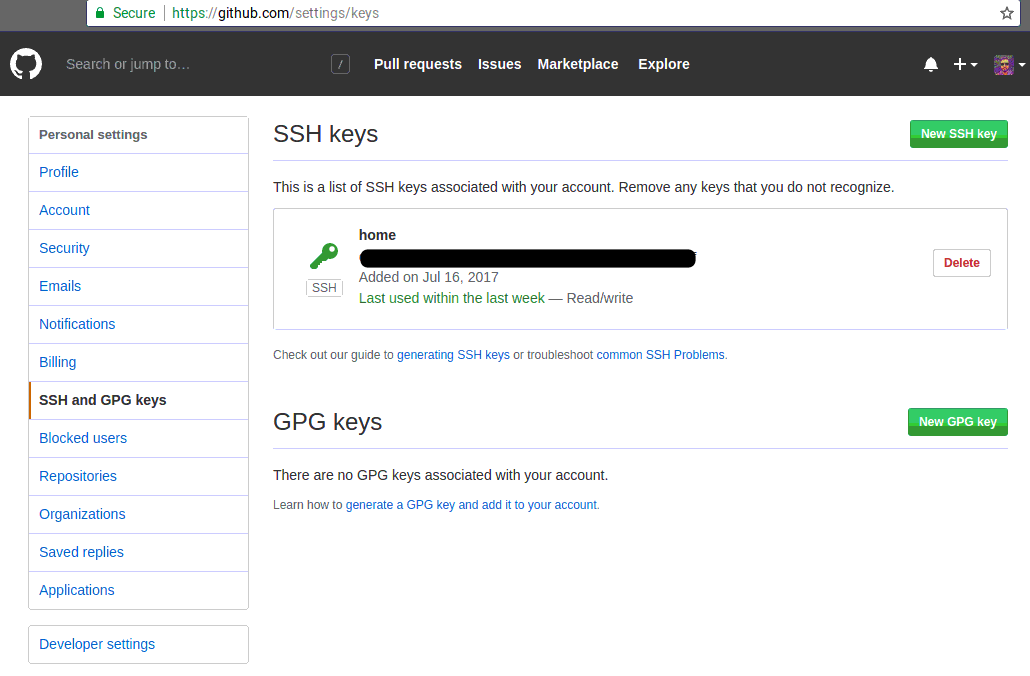

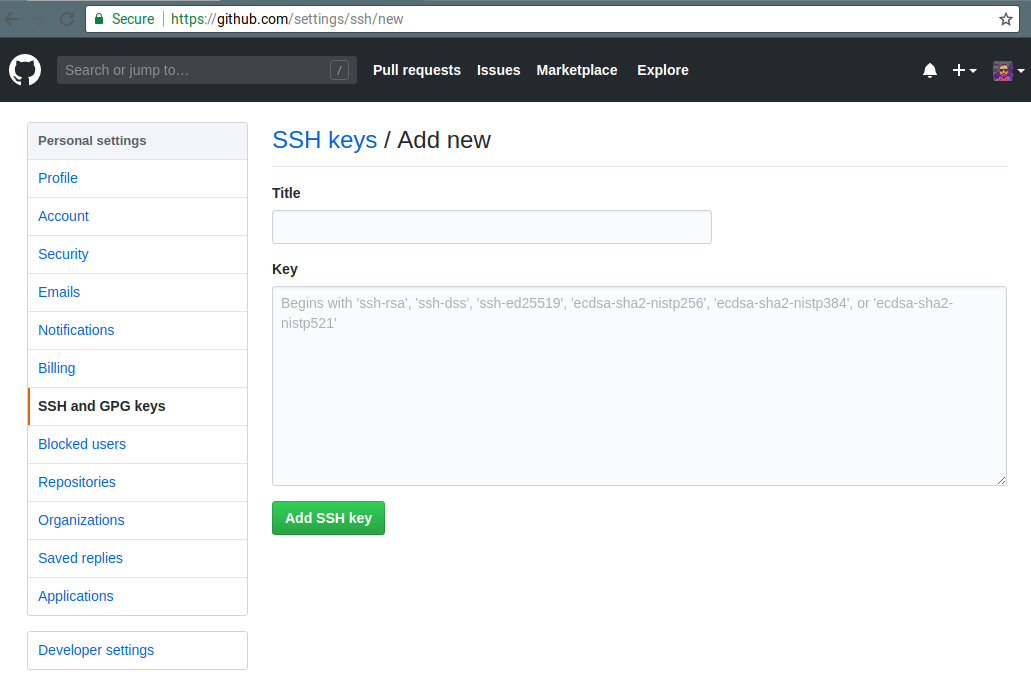

In order to share this package with these others we are going to use Git. If you’re familiar with Git, great, you’ll be able to skip some sections. If not, then buckle up, you’re in for a wild ride.

As I mentioned in the introduction, if you want to learn much more than I’ll show about packages read Wickham (2015). I will only show you the basics, but it should be enough to get you productive.

9.3 Including data inside the package

Many packages include data and we are going to learn how to do it. I’ll assume that we already have a dataset on hand that we have to share. This is quite simple to do, first let’s simply load the data:

arcade <- readr::read_csv("~/path/to/data/arcade.csv")and then use, once again, {usethis} comes to our rescue:

usethis::use_data(arcade, compress = "xz")that’s it! Well almost. We still need to write a little script that will allow users of your

package to load the data. This script is simply called data.R and contains the following lines:

#' List of highest-grossing games

#'

#' Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arcade_game#List_of_highest-grossing_games

#'

#' @format A data frame with 6 variables: \code{game}, \code{release_year},

#' \code{hardware_units_sold}, \code{comment_hardware}, \code{estimated_gross_revenue},

#' \code{comment_revenue}

#' \describe{

#' \item{game}{The name of the game}

#' \item{release_year}{The year the game was released}

#' \item{hardware_units_sold}{The amount of hardware units sold}

#' \item{comment_hardware}{Comment accompanying the amount of hardware units sold}

#' \item{estimated_gross_revenue}{Estimated gross revenue in US$ with 2019 inflation}

#' \item{comment_revenue}{Comment accompanying the amount of hardware units sold}

#' }

"arcade"Basically this is a description of the data, and the name with which the user will invoke the data. To

conclude this part, remember the data-raw folder? If you used a script to scrape/get the data

from somewhere, or if you had to write code to prepare the data to make it fit for sharing, this

is where you can put that script. I have written such a script, I will discuss it in the next

chapter, where I’ll show you how to scrape data from the internet. You can also save the file

where you wrote all your calls to {usethis} functions if you want.

9.4 Adding functions to your package

Functions will be added inside the R package. In there, you will find the hello.R file. You can

edit this file if you kept it or you can create a new script. This script can hold one function, or

several functions.

Let’s start with the simplest case; one function inside one script.

9.4.1 One function inside one script

Create a new R script, or edit the hello.R file, and add in the following code:

#' Compute descriptive statistics for the numeric columns of a data frame.

#' @param df The data frame to summarise.

#' @param ... Optional. Columns in the data frame

#' @return A data frame with descriptive statistics. If you are only interested in certain columns

#' you can add these columns.

#' @import dplyr

#' @importFrom tidyr gather

#' @export

#' @examples

#' \dontrun{

#' describe(dataset)

#' describe(dataset, col1, col2)

#' }

describe_numeric <- function(df, ...){

if (nargs() > 1) df <- select(df, ...)

df %>%

select_if(is.numeric) %>%

gather(variable, value) %>%

group_by(variable) %>%

summarise_all(list(mean = ~mean(., na.rm = TRUE),

sd = ~sd(., na.rm = TRUE),

nobs = ~length(.),

min = ~min(., na.rm = TRUE),

max = ~max(., na.rm = TRUE),

q05 = ~quantile(., 0.05, na.rm = TRUE),

q25 = ~quantile(., 0.25, na.rm = TRUE),

mode = ~as.character(brotools::sample_mode(.), na.rm = TRUE),

median = ~quantile(., 0.5, na.rm = TRUE),

q75 = ~quantile(., 0.75, na.rm = TRUE),

q95 = ~quantile(., 0.95, na.rm = TRUE),

n_missing = ~sum(is.na(.)))) %>%

mutate(type = "Numeric")

}Save the script under the name describe.R.

This function shows you pretty much you need to know when writing functions for packages. First,

there’s the comment lines, that start with #' and not with #. These lines will be converted

into the function’s documentation which you and your package’s users will be able to read in

Rstudio’s Help pane. Notice the keywords that start with @. These are quite important:

@param: used to define the function’s parameters;@return: used to define the object returned by the function;@import: if the function needs functions from another package, in the present case{dplyr}; then this is where you would define these. Separate several package with a space;@importFrom: if the function only needs one function from a package, define it here. Read it as from tidyr import gather, very similar to how it is done in Python;@export: makes the function available to the users. If you omit this, this function will not be available to the users and only available internally to the other functions of the package. Not making functions available to users can be useful if you need to write functions that are used by other functions but never be used by anyone directly. It is still possible to access these internal, private, functions by using:::, as in,package:::private_function();@examples: lists examples in the documentation. The\dontrun{}tag is used for when you do not want these examples to run when building the package.

As explained before, if the function depends on function from other packages, then @import or

@importFrom must be used. But it is also possible to use the package::function() syntax like

I did on the following line:

mode = ~as.character(brotools::sample_mode(.), na.rm = TRUE),This function uses the sample_mode() function from my {brotools} package. Since it is the only

function that I am using, I don’t import the whole package with @import. I could have done the

same for gather() from {tidyr} instead of using @importFrom, but I wanted to showcase

@importFrom, which can also be use to import several functions:

@importFrom package function_1 function_2 function_3The way I’m doing this however is not optimal. If your package depends on many functions from

other packages that are not available on CRAN, but rather on Github, you might want to do that

in a cleaner way. The cleaner way is to add a “Remotes” field in the package’s NAMESPACE (this is

a very important file that gets generated automatically by devtools::document()) I won’t

cover this here, but you can read more about it here.

What I will cover is how to declare dependencies to other CRAN packages. These dependencies also

get declared inside the ‘Description’ file, which we will cover in the next section.

Because I’m doing that in this hacky way, my {brotools} package should be installed:

devtools::install_github("b-rodrigues/brotools")Again, I want to emphasize that this is not the best way of doing it. However, using the “REMOTES” field as described in the document I linked above is not complicated.

Now comes the function itself. The function is written in pretty much the same way as usual, but

there are some particularities. First of all, the second argument of the function is the ..., which

were already covered in Chapter 7. I want to give the option to my users to specify any columns to

summarise only these columns, instead of all of them, which is the default behaviour. But because

I cannot know how many columns the user wants to summarize beforehand, and also because I do not

want to limit the user to 2 or 3 columns, I use the ....

But what if the user wants to summarize all the columns? This is taken care of in this line:

if (nargs() > 1) df <- select(df, ...)nargs() counts the number of arguments of the function. If the user calls the function like so:

describe_numeric(mtcars)nargs() will return 1. If, instead, the user calls the function with one or more columns:

describe_numeric(mtcars, hp, mpg)then nargs() will return 2 (in this case). And does, this piece of code will be executed:

df <- select(df, ...)which selects the columns hp and mpg from the mtcars dataset. This reduced data set is then

the one that is being summarized.

9.4.2 Many functions inside a script

If you need to add more functions, you can add more in the same

script, or create one script per function. The advantage of writing more than one function per

script is that you can keep functions that are conceptually similar in the same place. For instance,

if you want to add a function called describe_character() to your package, adding it to the same

script where describe_numeric() is might be a good idea, so let’s do just that:

#' Compute descriptive statistics for the numeric columns of a data frame.

#' @param df The data frame to summarise.

#' @param ... Optional. Columns in the data frame

#' @return A data frame with descriptive statistics. If you are only interested in certain columns

#' you can add these columns.

#' @import dplyr

#' @importFrom tidyr gather

#' @export

#' @examples

#' \dontrun{

#' describe(dataset)

#' describe(dataset, col1, col2)

#' }

describe_numeric <- function(df, ...){

if (nargs() > 1) df <- select(df, ...)

df %>%

select(is.numeric) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable", values_to = "value") %>%

group_by(variable) %>%

summarise(across(everything(),

tibble::lst(mean = ~mean(., na.rm = TRUE),

sd = ~sd(., na.rm = TRUE),

nobs = ~length(.),

min = ~min(., na.rm = TRUE),

max = ~max(., na.rm = TRUE),

q05 = ~quantile(., 0.05, na.rm = TRUE),

q25 = ~quantile(., 0.25, na.rm = TRUE),

mode = ~as.character(brotools::sample_mode(.), na.rm = TRUE),

median = ~quantile(., 0.5, na.rm = TRUE),

q75 = ~quantile(., 0.75, na.rm = TRUE),

q95 = ~quantile(., 0.95, na.rm = TRUE),

n_missing = ~sum(is.na(.))))) %>%

mutate(type = "Numeric")

}

#' Compute descriptive statistics for the character or factor columns of a data frame.

#' @param df The data frame to summarise.

#' @return A data frame with a description of the character or factor columns.

#' @import dplyr

#' @importFrom tidyr gather

describe_character_or_factors <- function(df, type){

df %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable", values_to = "value") %>%

group_by(variable) %>%

summarise(across(everything(),

funs(mode = brotools::sample_mode(value, na.rm = TRUE),

nobs = length(value),

n_missing = sum(is.na(value)),

n_unique = length(unique(value))))) %>%

mutate(type = type)

}

#' Compute descriptive statistics for the character columns of a data frame.

#' @param df The data frame to summarise.

#' @return A data frame with a description of the character columns.

#' @import dplyr

#' @export

#' @examples

#' \dontrun{

#' describe(dataset)

#' }

describe_character <- function(df){

df %>%

select(where(is.character)) %>%

describe_character_or_factors(type = "Character")

}Let’s now continue on to the next section, where we will learn to document the package.

9.5 Documenting your package

There are several files that you must edit to fully document the package; for now, only the functions

are documented. The first of these files is the DESCRIPTION file.

9.5.1 Description

By default, the DESCRIPTION file, which you can find in the root of your package project, contains

the following lines:

Package: arcade

Type: Package

Title: What the Package Does (Title Case)

Version: 0.1.0

Author: Who wrote it

Maintainer: The package maintainer <yourself@somewhere.net>

Description: More about what it does (maybe more than one line)

Use four spaces when indenting paragraphs within the Description.

License: What license is it under?

Encoding: UTF-8

LazyData: true

RoxygenNote: 7.0.2Each section is quite self-explanatory. This is how it could look like once you’re done editing it:

Package: arcade

Type: Package

Title: List of highest-grossing Arcade Games

Version: 0.1.0

Author: person("Harold", "Zurcher", email = "harold.zurcher@madisonbus.com", role = c("aut", "cre"))

Description: This package contains data about the highest-grossing arcade games from the 70's until

2010's. Also contains some functions to summarize data.

License: CC0

Encoding: UTF-8

LazyData: true

RoxygenNote: 7.0.2The Author and Maintainer need some further explanations; I have added Harold Zurcher as

the athor and creator, with the role = c("aut", "cre") bit. "cre" can also be used for

maintainer, so I removed the Maintainer line.

References

If you know who Harold Zurcher is, you da real MVP↩︎